CBP One’s obscene language errors create more barriers for asylum seekers

By Leila Lorenzo, Laura Wagner, Ariel Koren, Juan Camilo Mendez

Since its launch in October 2020, U.S. Customs and Border Protection has required asylum seekers at the southern border to use the agency’s CBP One mobile app to schedule their appointments to enter the country.

Prior to CBP One’s launch, asylum-seekers and individuals seeking humanitarian parole would have worked with an organization to submit their parole application. Today, CBP One has become the primary way in which asylum seekers can secure an appointment at ports of entry and maintain guaranteed asylum eligibility. Requests made through the CBP One app go directly to U.S. immigration officials and do not involve other organizations, shelters, or attorneys.

Since its introduction and implementation, the CBP One app has become another cruel obstacle in an already dysfunctional asylum and immigration system to safety, dignity, freedom of movement, and language access, according to research by Respond Crisis Translation. This reality has been repeatedly documented by major human rights organizations such as Amnesty International, which has called the app a violation of the right to seek asylum. Among its many problems, the app is beset with so many language issues it is virtually unusable by most asylum seekers. This has inhumane consequences for those most vulnerable.

The U.S. Departments of Homeland Security and Justice have required that asylum seekers who arrive at the southern border of the United States use CBP One to schedule a time and place to present themselves at a port of entry, lest they face a “rebuttable presumption,” rendering them ineligible for asylum. While the rule also allows asylum seekers an exception if they can show that they could not access or use the app’s scheduling system “due to language barrier, illiteracy, significant technical failure, or other ongoing and serious obstacle,” this standard is arbitrary and vague and the process for reaching it inconsistent and inaccessible.

The CBP One app and the rules mandating its use represent dangerous affronts to human rights; the “serious obstacles” presented by the app are not fringe exceptions, but rather the rule. A Respond review of the app revealed that its indisputable language incompetency erects more institutionalized barriers to asylum than the app supposedly solves. These include its extremely limited offering of languages, nonsensical translations, and glitches and other digital barriers.

Languages offered

CBP One has only been offered in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole. This limited offering does not reflect the vast diversity of those spoken among asylum seekers and fails to reflect the changing demographics of immigrants at the US-Mexico border. Forty years ago, most immigrants arriving at the border came from Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala. According to the Migration Policy Institute, we have entered an era in terms of the demographics of new arrivals. Geopolitical events have resulted in larger numbers of Afghan, Ukrainian, Congolese, Syrian, Myanmar, Indian, Turkish, and Chinese nationals, the last of whom comprise the fastest growing group entering the United States at the southern border. Given that less than 15% of immigration court cases are conducted in English, the scant language offerings and poor translations contained within CBP One are wholly unacceptable.

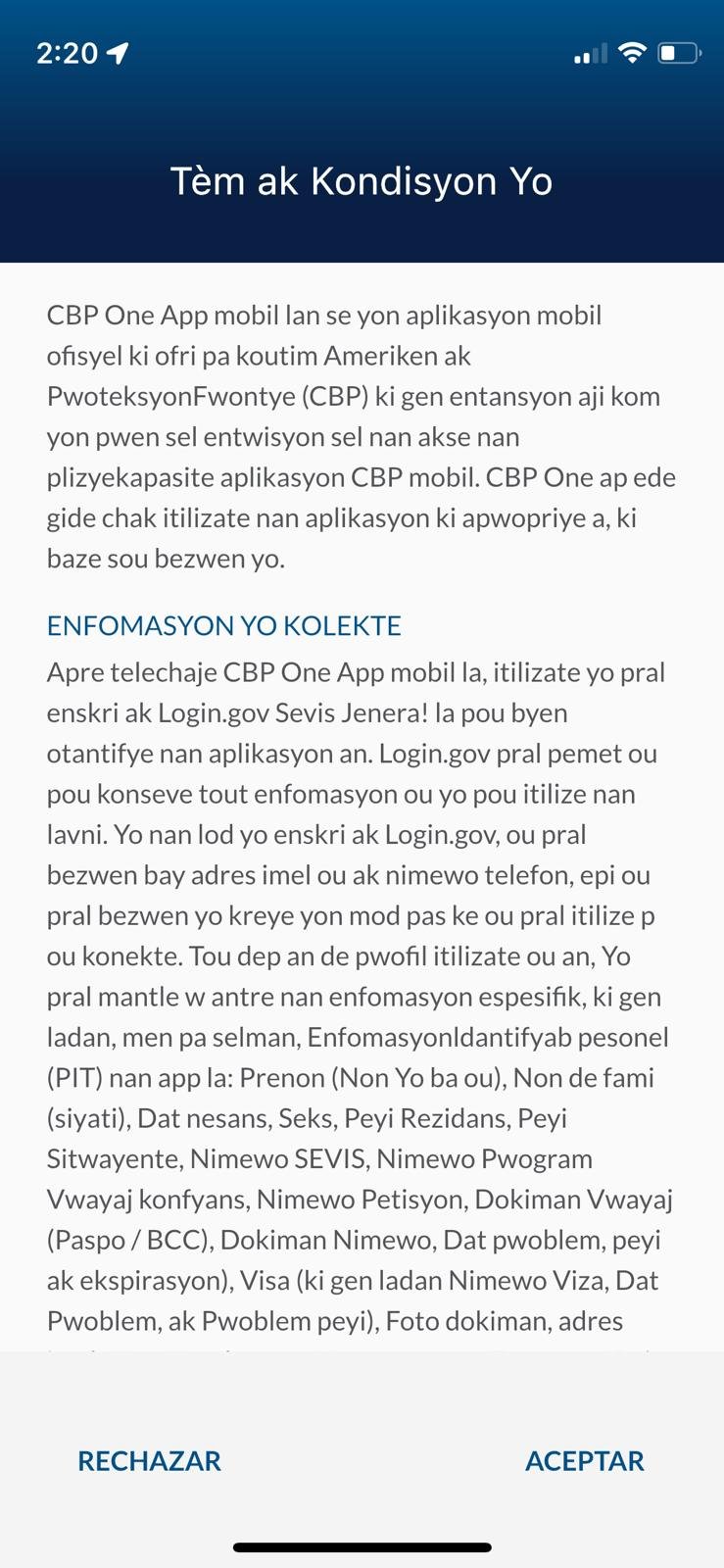

A screenshot of the Haitian Creole Terms and Conditions page incorrectly translates the “customs” in U.S. Customs and Border Protection to “koutim” (traditions). The rest of the page is nonsensical.

Nonsensical translations

CBP One is only offered in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole – significantly disadvantaging the many asylum seekers who do not speak these languages. Even among the non-English languages offered, the many errors make it unusable.

These errors are as basic as they are numerous.

In Haitian Creole, the app mistranslates the name of the agency.

The app uses the incorrect word for “Customs” in its Haitian Creole translation of “Customs and Border Protection” –“koutim” instead of “ladwan.”

However, the word “koutim” refers to social customs and traditions, not to trade and the immigration system.

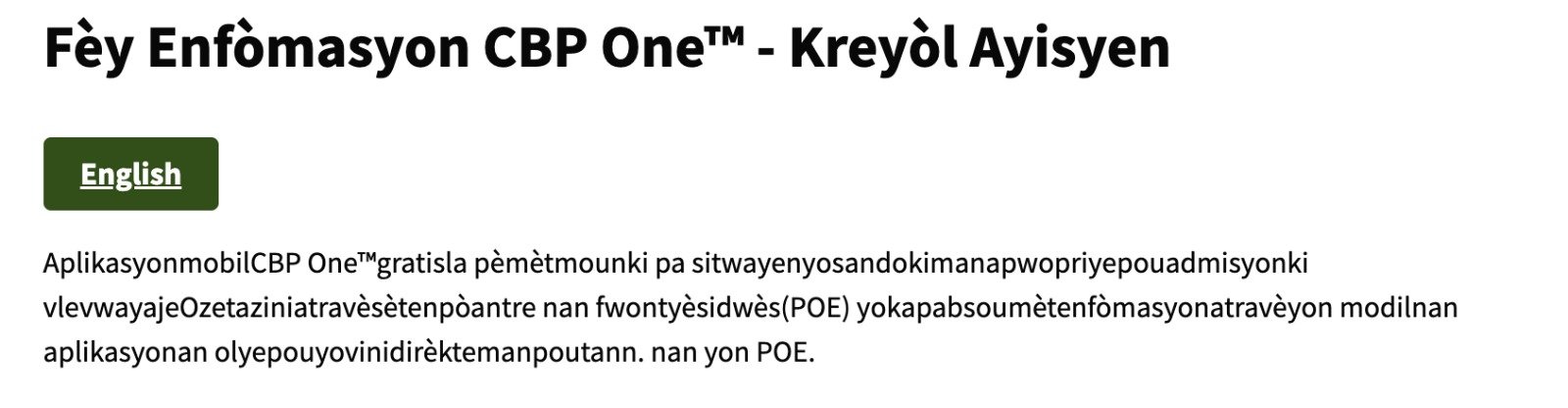

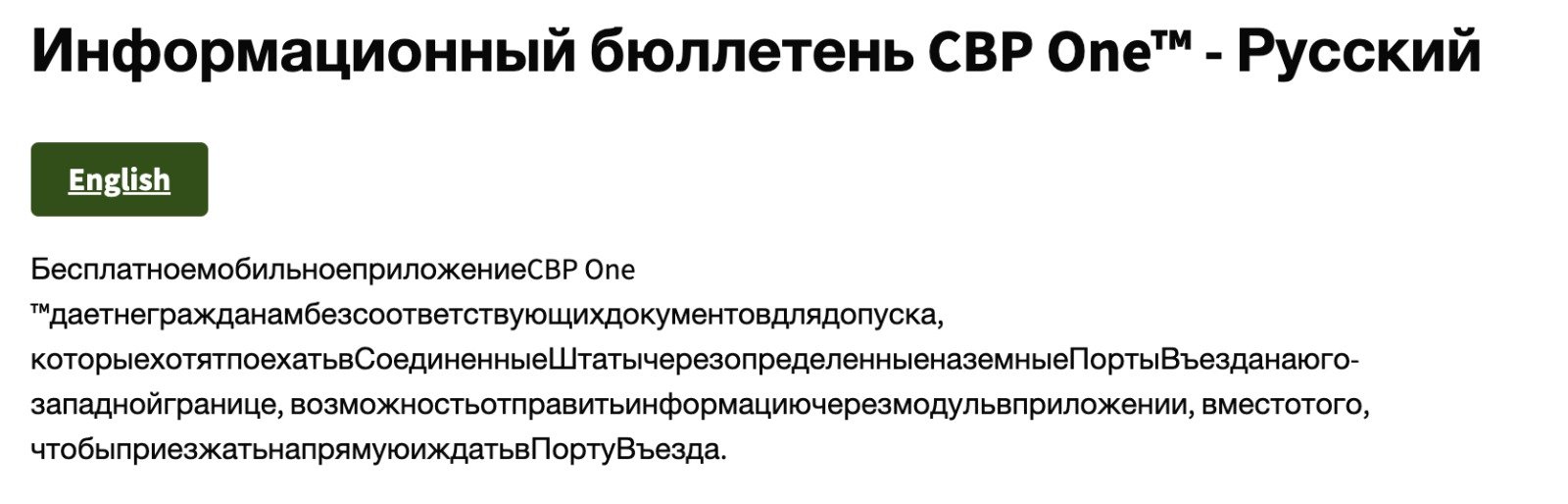

Orthographic errors like the absence of spaces between words creates a nonsense string of letters in the Haitian Creole and Russian CBP One factsheets, making them impossible to understand.

The Haitian Creole CBP One factsheet is a nonsense string of letters due to missing spaces.

The Russian CBP One factsheet is also unintelligible due to orthographic errors.

To even access the Haitian Creole version of the app, one must answer several questions in English or Spanish, and not every page in the Spanish version of the app appears to be properly or completely translated.

Respond has also documented CBP’s deeply concerning use of machine translation (MT). CBP’s use of MT renders critical information unintelligible to many asylum seekers through distorting meaning, inaccurate translations, and orthographic errors (see Appendix I for examples). MT has likely also been used on the CBP One app, a significant problem given that MT performs inconsistently and unreliably across languages.

Glitches and other digital barriers

There are also a number of additional problems with CBP One that demonstrate how the app has created new digital barriers to asylum generally.

There are numerous reports of “glitches” and crashes with CBP One, an inevitable consequence of a political decision to force already vulnerable asylum seekers to depend upon experimental technologies that impede rather than facilitate their asylum-seeking process.

For example, as of June 2023, 1,450 new appointments are available for 23 hours each day through the app. Efforts by refugee-serving organizations document that the average wait time is one to two months, effectively making asylum seekers compete for appointments. Because cities by the border often have shelters filled beyond capacity, many wait for appointments in camps and face the risk of violence and persecution as they wait.

Additionally, other technological obstructions, such as a lack of smartphones and unreliable access to internet or electricity create additional obstacles for asylum seekers at the border. CBP One also raises privacy, discrimination, due process, and surveillance concerns due to its facial recognition technology that fails to recognize non-white skin tones and the app’s ability to collect data about the locations of asylum seekers.